Writing

I. Sign

There’s a sign above the highway near my hometown that reads “Sacramento Ca 3073.” It’s posted above U.S. Route 50 at its eastern origin, an old drawbridge that leads into town. We fished from this bridge as kids, a few hundred yards from the Atlantic Ocean. My first memory of the sign goes back to 1979, when a childhood friend pointed to it, “Lets drive to California when we’re finished high school,” he said. The idea of the West existed only as a dream for us in those days.

I didn’t think about the sign for a long time, until many years later in the fall of 2000. Newly married, I had just moved to the West Coast and was passing through California. I was on the interstate when it appeared in the distance: “Ocean City MD 3073,” a corresponding road sign to the one I’d grown up with on the other side of the continent. I was at the other end of the highway.

I was caught off guard by the sight, and suddenly recalled the day my friend and I stood beneath the sign back home. I wondered what he would make of this endpoint—a dusty tangle of freeway on the outskirts of Sacramento. The sign has fixed itself in my mind in the many years since that day in California, and will serve here as the beginning of this story.

I hadn’t seen that childhood friend for twelve years previous to that day on the freeway in Sacramento. He had pled guilty to murder and was now serving 25 years at the new state prison not far from where we grew up. I’d last seen him a couple years before the crime in the late 80’s while on break from art school when he replaced the water pump on my pickup truck. I was in a rush to get back to school in Baltimore and short on cash so he did it for free.

Before I left his house that night we had coffee in his kitchen, and I saw hanging above the fireplace in the den the painting his father had bought from me when I was thirteen. It was a painting of the “Fenwick Light,” a local lighthouse, the first I ever sold. I used that money to buy a full set of “professional artist” paints. We saw less and less of each other in high school as our interests diverged. Senior year I received a scholarship to attend art school in Baltimore, and our lives continued to move apart.

What I remember most about that night having coffee was staring at a trash bag on the kitchen floor with a deer antler sticking out. “Thawing to mount,” he said. Blood was dripping down the dark plastic and gathering into a puddle on the floor. After art school I moved away for good, and we fell out of touch.

In 2001, I lost my job and separated from my wife. “I need space, please, at least give me that” and, “I’ve been having self-destructive thoughts,—-” she said. In desperation, I called a suicide hotline looking for advice. I was on the line for more than an hour, but they never seemed convinced that it wasn’t me planning to kill myself.

“Crash on my sofa until she cools off,” advised Mike, a friend in our new neighborhood who usually made his living working on fishing boats up in Alaska. I spent the next couple weeks at his house, waiting out the “rough patch” as he called it.

“I really don’t have time to deal with all of this right now” she said over the phone. “I’m under a lot of stress at work.” Shortly after that she stopped returning my calls. I struggled to hold it together.

“Why don’t you come back home for a while and get your head on straight. It would do you some good,” my mother pleaded with me. So I got on a plane and flew east for what I intended to be a temporary stay, though I was uncertain when I’d return.

I spent those long days in my hometown driving around aimlessly and thinking, searching for old friends and trying to figure out a way forward. A new freeway had gone in since I’d been there last, slicing through farmland and turning familiar old roads into dead ends. Most of my friends had moved on. I felt disoriented and depressed.

How are things out on the Left Coast . . . selling any paintings?” asked my younger cousin. He had become very successful selling firearms on the internet, a respected local businessman in the new economy. I told him my marriage was falling apart. “You should move back here and come to work for me. I’ll put you in the warehouse. Business is booming.” He meant it as a joke, but could see I considered it for a moment. There was an awkward pause. “. . . it’s all about the internet now. You need to get on board . . . .” Then, “I gotta run . . . keep me posted.” He pulled away, blowing the horn and giving a thumbs up. He was driving a new Hummer with darkened windows.

Later that day I discovered that the farmhouse I lived in the summer after graduating high school had vanished—burned to the ground. Just the blackened cellar remained as a perfect monument to its subtraction from the landscape. Cement steps descended into a dark pool of water—a fitting image for my state of mind.

Years before I found an arrowhead in the field behind this house and had kept it all this time as a good luck charm. Carved from white quartz, it was in my desk drawer, polished and in a box, far away on the west coast. What I wanted more than anything that day was to return it to where it belonged, in the field near where I stood— a field that would soon become a golf course and housing development. It was then that I realized I needed to visit the state prison and see first-hand where my childhood friend was now an inmate.

And so with no real plan, I borrowed my father’s pickup the next morning and drove to the new penitentiary. He offered directions while unclipping the keys from his belt, “Best go the back way through the state woods,” he said, handing me the keys. I took his advice. I went for myself mostly because I was curious. But the trip felt predestined—somehow I sensed that seeing the prison might help resolve the feelings of futility and regret trapped inside my head. Had I made a great mistake by leaving this place, among the people that I love? What would be different had I remained?

I knew I wouldn’t be able to see my friend that day, this came later, but I took a small sketch pad and my old 35mm camera. I am a painter—of landscapes mostly—and I didn’t know it then, but this would be the first of many trips to prison towns over the years ahead whose scenes would become the basis of my work. I had little understanding of the prison system then, and I have little more understanding of it now.

II. River

The past is never dead. It's not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity. Haunted by wrong turns and roads not taken, we pursue images perceived as new but whose providence dates to the dim dramas of childhood, which are themselves but ripples of consequence echoing down the generations. The quotidian demands of life distract from this resonance of images and events, but some of us feel it always. ~ William Faulkner

The new prison is near a neighboring town much like the one I grew up in, and the drive took me through the state forest and across the Pocomoke River. Modest homes with laundry on the line and familiar clutter in back yards; the old county courthouse; a church missing its steeple beside a group of leaning headstones; a public park with a skate bowl behind chain link fence; then the high school visible from across a football field.

Controversial from its inception, the prison came with the promise of well-paying jobs and critical tax revenue for the “weak rural economy,” and was opposed by many nearby residents. A Historically Black College is located about five miles away from it. I remember reading about the prison proposal controversy at the time in a small local newspaper, which has since closed. The current warden had been in my chemistry class in high school. At least two other classmates I knew were working there as guards: several other classmates were inmates. The prison has remained controversial.

On the edge of town I stopped to cross the interstate and saw the lights of the penitentiary in the distance rising high above the trees. Waiting for the traffic light to turn green, I watched a steady stream of out of state cars topped with surfboards and camping gear rush past on the highway on their way to Assateague Island National Park and the coast.

Young trees concealed the facility until I was about 20 yards from the perimeter fence. “No stopping or standing. State property” read the signs just ahead. I pulled to the side of the road as a nearby watchtower looked on.

Veiled by chain link and razor wire, the prison complex was a sprawling campus of concrete bunkers displaying the same grim inevitability as many institutional buildings. Closely resembling a military installation, the low-slung cell blocks were entirely without ornament and seemed to have risen from the landscape rather than to have been built upon it. Two rows of vertical slotted windows were cut deep into the beige cell blocks. Several thousand people were behind those windows, but not a single person was in sight.

The prison was and still is the largest in the state, with a population exceeding 3,000 people—more than the population of the town I grew up in. From inside the truck, I made a quick drawing and took some photographs. The sketch was a small act of bearing witness—by drawing a place designed to disappear.

A few hundred feet north of the prison, a small creek with water the color of old pennies flows through the woods. A short distance downstream, the creek joins the Manokin River, which meanders 15 miles southwest before flowing into Tangier Sound and opening up to the brackish waters of the Chesapeake.

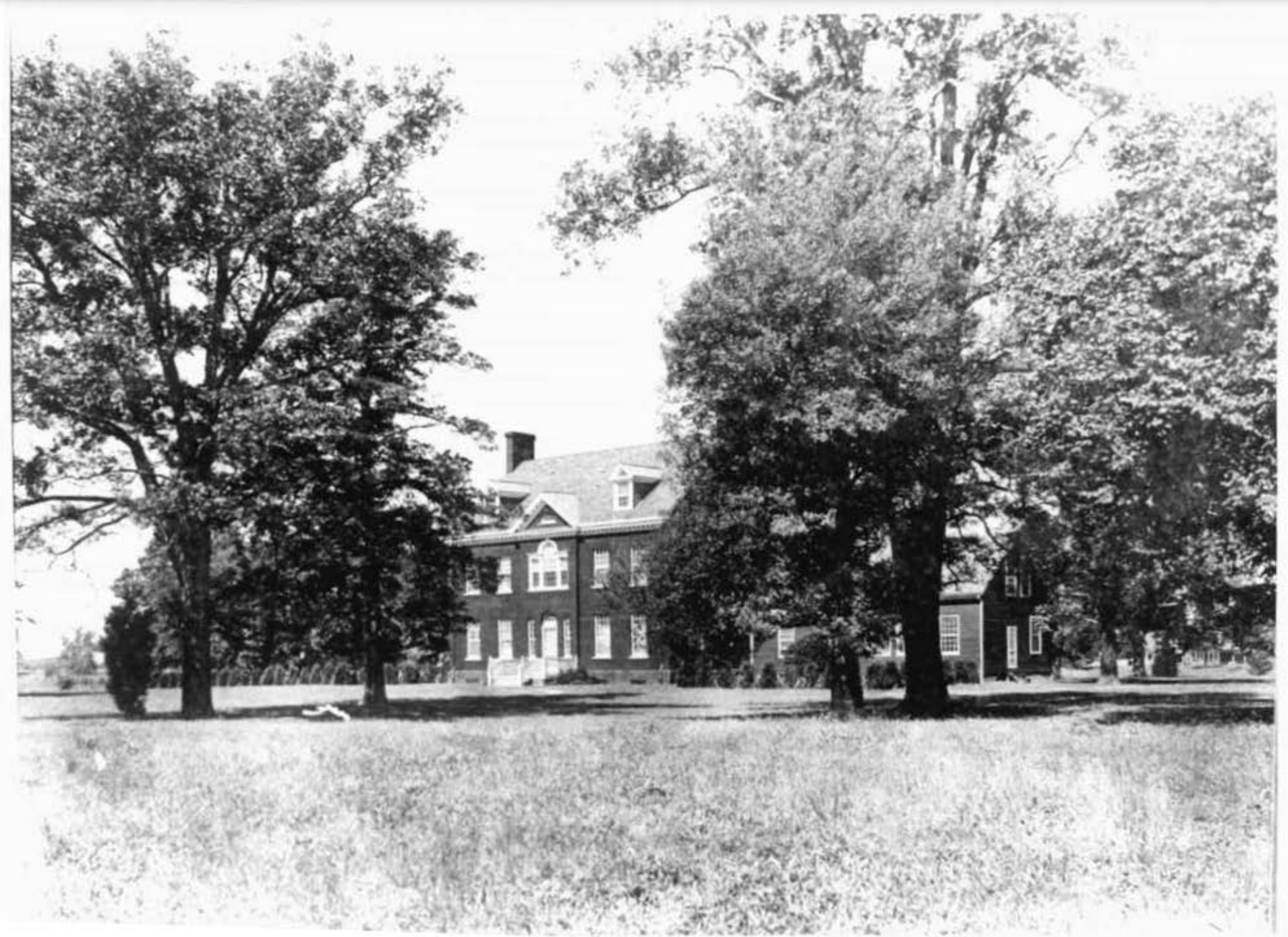

The Manokin is a waterway deep with history. Some of the houses on it have been there for centuries, dating from a time when plantations lined its marshy shores. Many buildings in the area are designated as historic landmarks, with roadside signs explaining the significance of their presence. In the lush green landscape, the faded red of their brick is called out by the morning sun, giving a lightness to their color that belies the gravity of their history. Framed by red cedar and honey locust trees, the houses appear unchanged from their genteel past. They are often used these days to host weddings or as bed and breakfasts.

Here, on the peninsula that forms Maryland’s Eastern Shore, the sunlight has a distinct warmth to its color in the spring, with a slightly yellow cast, growing cooler in tone near open water, which is never far away.

I took a last look at the penitentiary swathed in this idyllic light, and thought of my old friend inside and the thousands of other souls within those walls. How did we get to this place, where a prison like this would become so accepted, such a normal part of the landscape we live in? Though the lives inside were invisible to me, I knew that the events in my life were as random and mysterious as the events experienced by anyone serving time there. I put the truck into gear as a rush of fear washed through me. I checked the rear-view mirror while pulling away, the anxiety easing slightly as my distance from the prison grew.

Driving away I heard gunfire from the state police firing range and passed the county animal control facility. In the flat fields nearby, farm workers picked strawberries for market somewhere far from here. It was spring and a bank of clouds threw shadows across the road ahead. Turkey vultures hovered on the thermals above, and I could see the silo of the local poultry plant over the trees to the south.

About halfway home I crossed back over the Pocomoke River as a group of kayakers passed under the bridge in brightly colored plastic boats, a small dog riding forward in one, barking into the dark water. My friend had disposed of his murder weapon here, throwing it into the river from the open window of his car the night of the crime.

The river’s name “Pocomoke” translates as “broken ground” in the Algonquin language. Three centuries ago, historians say, on an island far up this waterway, the last great meeting of local tribes took place before the majority of indigenous people departed this area, never to return. Some few natives remained behind, and were assimilated into the European way of life, their culture lost to the ages. A hundred years ago the river was cut and dredged to drain the surrounding wetlands, but its tannic waters are still fed by what is known as the “Great Cypress Swamp” to the north. Locals call it the “burnt swamp” because of the subterranean wildfires that at one time burned for years in its peat bogs.

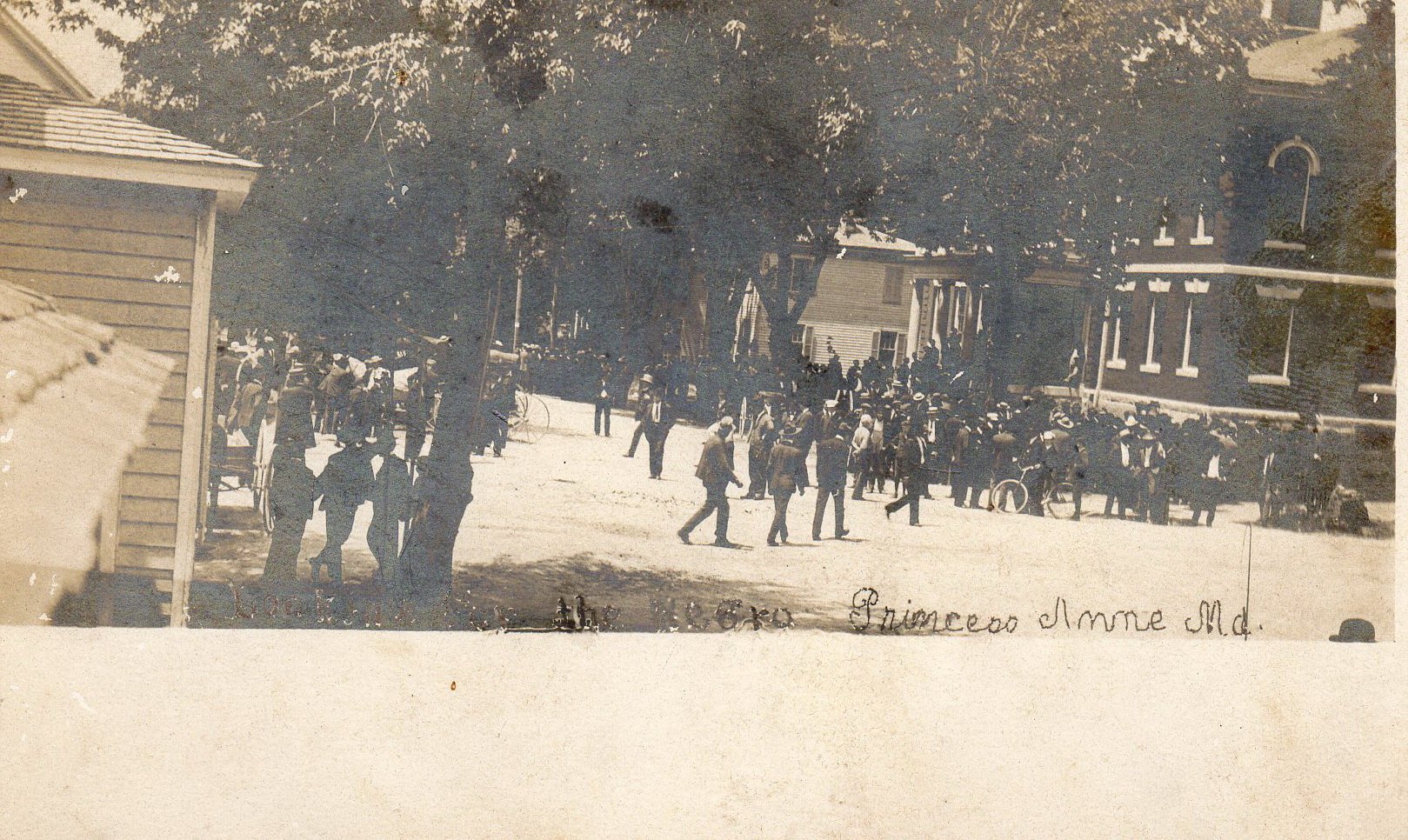

My grandmother told stories about the fires, still superstitious about the swamp and its dangers many years later. Her stories usually featured an Old Testament sense of morality and vengeance. She had been alive when the lynching took place at the county jail here almost 90 years ago, though she never spoke of it. Twelve white men were later tried for the crime: all were acquitted. That same year she gave birth to my father, in the front room of the farmhouse where he grew up, 30 miles northeast of where the prison now stands.

Further down the road I passed an old shed snarled in greenbrier, a hand-painted sign posted beside it read, “fresh eels for sale.” I made a left turn just after and entered the state forest, wondering for a moment if selling fresh eels would be more lucrative than selling paintings.

Driving through the woods, windows down, the smell of pine filled the truck’s interior, comforting me. I drew a deep breath and considered this place, wondering what the landscape would say if it could speak. All landscapes have memories: this one is no different.

The sheltered harbors and fertile lands here have been attractive to land speculators since the Virginia Company representatives sighted its shores 400 years ago. My ancestors landed a couple of decades later, and were awarded land nearby for their seven-years servitude. Other immigrants and their descendants were not as fortunate. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglas were both born into bondage on this peninsula. Both escaped to freedom in the North.

This coastal plain is a landform that is nothing more than a massive sandbar, with shorelines that constantly shift, tracing thousands of miles along the contours of intricate estuaries.

The landscape was created by millennia of glacial runoff through prehistoric tropical river valleys on its way to the sea. The waters flowed over mountains far inland, and carried sediment that slowly filled the valleys, resulting in the gentle topography we see today. Flat and deeply forested, the soils are fertile but sandy, with granite basement-rock far below. I thought of my family, and the many generations whose bones rest in the sandy soil of this peninsula.

Somewhere in the forest, I made a wrong turn and wound up near the county landfill, which had recently become the highest point of elevation in the county. I smell its odor before I see it, crying seagulls visible now above the trees. Meanwhile, in the reaches of my mind, the dark flow of sadness and regret was beginning to fade away. I made a three-point turn on the narrow gravel road, turned around, and slowly found my way back to the main highway.